Mouth of Sungei Serangoon, which has since been dammed up to create the Serangoon Reservoir;

(Photo by Food Trails)

Hello from SG (@HellofrmSG), Singapore's very own rotation curation project on Twitter, has just been launched, and our very first curator is journalist and history buff Eisen Teo (@eisen).

As part of his self-introduction, Eisen shared the etymology of the name of his neighbourhood, Serangoon:

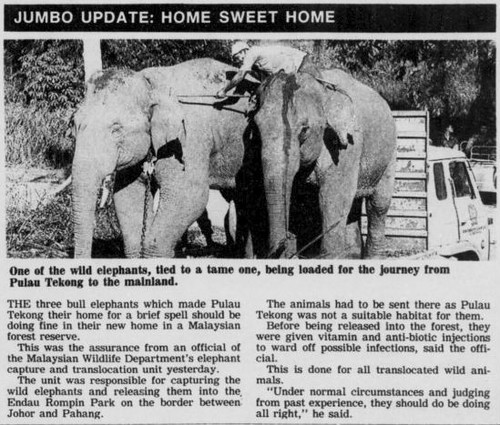

(Note: an alternative explanation is provided in the 27th March 1950 edition of The Straits Times)

Naturally, this piqued my interest. Just what sort of bird did the Malay name burong ranggong refer to?

A Google search for "burong ranggong" wasn't very helpful, as all it did was turn up various other sites with similar explanations as to how Serangoon got its name. However, some of these provide further information; for instance, if you combine the clues given by this page from the Singapore Tourism Board, and this page from the National Libary Board, the burong ranggong is apparently a "small, black and white marsh bird."

There are a few local birds that are clearly black and white, such as the Oriental magpie robin (Copsychus saularis), Oriental pied hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris), or white-bellied sea eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster). One species in particular, the white-breasted waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicurus), lives close to water, and is usually encountered near dense vegetation in marshes and swamps. Could this be the burong ranggong that Serangoon was named after?

White-breasted waterhen, Singapore Botanic Gardens;

(Photo by mjmyap)

Unfortunately, no. According to the Bahasa Malaysia edition of Wikipedia, the white-breasted waterhen is burung ruak-ruak.

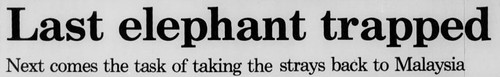

Other sources refer to the burong ranggong (also spelt burung ranggung) as some sort of stork. A 1934 article from The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser states that

...The Serangoon district, spelt Saranggong in old land grants, deeds and legal conveyances, is a derivation of "Sa Ranggong," "ranggong" being a species of adjutant stork. I understand that that part of Singapore was the habitat of that particular breed of bird. It should be noted that the Malay prefix, "Sa," means, "one of anything."That does a lot to clarify a lot of the confusion.

The name "adjutant" refers to 2 large species of stork found in tropical Asia, the greater adjutant (Leptoptilos dubius) and lesser adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus).

Greater adjutant, India;

(Photo by yathin)

These are related to the more famous (and extremely ugly) marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumeniferus) of Africa.

Marabou, Kenya;

(Photo by -Ni'ma-)

Among the 2 adjutant storks, it is the lesser adjutant which can be found in the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia, and in fact, this species was recorded from Singapore in the past. Could it be that Serangoon owes its name to this inhabitant of wetlands and mangroves?

Lesser adjutant, Johor;

(Photo by Lip Kee)

However, the lesser adjutant is a large bird that can grow up to 1.2 metres in height, with a wingspan of 2 metres. It's certainly not a "small" marsh bird, and makes one wonder how that error came about!

(Photo by yychong)

Lesser adjutant storks are distributed from India and Sri Lanka to Indochina, the Malay Peninsula, and the islands of Sumatra, Borneo and Java. An opportunist, this bird feeds on all sorts of small animals; fishes, frogs, and crustaceans are taken, as are rodents and small birds. Unlike the greater adjutant and marabou however, which have adapted to feeding on human refuse and are well known as scavengers, the lesser adjutant is said not to consume a lot of carrion in comparison.

(Photo by Rainbirder)

Globally, this species is considered Vulnerable to extinction; hunting of adults and harvesting of eggs and chicks occurs, but perhaps the more significant threat comes from habitat loss and degradation, including the draining of wetlands for aquaculture, development, and changing agricultural practices, which often includes the liberal use of pesticides. As these storks nest in colonies, the loss of available trees in their habitual breeding grounds and human disturbance have also been implicated as factors behind drastic declines or even extirpation of the lesser adjutant from many parts of its range.

(Photo by rayanLEE)

According to a 2009 paper, The status of the lesser adjutant stork (Leptoptilos javanicus) in Singapore, there is very little information about lesser adjutant storks in Singapore during the colonial period; the only records that we know of include that of a resident pair in the Tanglin area in 1882, and of unconfirmed breeding reports from the outskirts of town, in 1938. Unfortunately, there's nothing that conclusively states that the lesser adjutant once lived in what we now know as the Serangoon area. In 1986, a lesser adjutant was indeed seen in Serangoon, but it had its wings clipped, and was clearly a former captive.

So while I think we've found the most likely candidate for the burung ranggung that gave Serangoon its name, there are no statements from naturalists or ornithologists from the late 18th and early 19th centuries to confirm this.

(Photo by Vijay Anand Ismavel)

The lesser adjutant is listed as locally extinct in Singapore, although populations can be found in the mangroves and mudflats of western Johor. Lesser adjutants have been regularly encountered between Kukup and Tanjong Piai, and the latter is within sight of Tuas. Villagers at Kampong Pendas, near the Second Link, have also reported at least 2 birds in the area. So it's certainly conceivable that once in a while, individuals may fly across to the western coasts of mainland Singapore.

(Photo by Rivertay)

Indeed, this is what has happened, with sightings at Sungei Buloh in 1999, and a number of records from near the coast of the Western Catchment, which is part of a military training area and off-limits to most members of the public.

A lone lesser adjutant on the coastal dyke adjacent to Poyan Reservoir near the PUB Tanjong Skopek sluice gates on 9 Sep 2008;

A lone lesser adjutant on freshwater marshes at the Pergam Channel linking Murai and Poyan Reservoirs on 14 Jan 2009, after another individual flew inland;

(Photos by R. Subaraj)

Hopefully, given enough time, minimal disturbance, as well as upcoming plans to link disjointed patches of mangroves as part of the Sungei Buloh Master Plan, these storks will establish themselves here, and form a new breeding population.

(Photo by Arddu)

An interesting side note: I tried searching for burung ranggung in the Malay Wikipedia, and the only result is a redirect to burung botak padi, which is apparently the Malay name for milky stork (Mycteria cinerea). This list of bird names in Malay has burung ranggung padi, which similarly redirects to the entry for milky stork. The Malay name for lesser adjutant is supposedly burung botak kecil. I have a feeling that burung ranggung has fallen out of favour, and has been replaced by burung botak as the 'official' term to refer to storks.

Milky stork, Japanese Garden;

(Photo by kampang)

Like the lesser adjutant, the milky stork is widely distributed across Southeast Asia, although it too is now declining and its status is Vulnerable. Often seen at Sungei Buloh and the Japanese Garden, these storks are actually free-flying birds from the Singapore Zoo and Jurong Bird Park which not only regularly wander beyond the park compounds to feed, but have also managed to breed. There are no records of the milky stork ever having occurred here naturally in the past, although it was once present in greater numbers and had a much wider distribution in Peninsular Malaysia.

(Photo by eddylynx)

Similarly, flocks of the closely related painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala), often seen at Sungei Buloh or in the vicinity of the Singapore Zoo, are of captive origin. This species is globally Near-Threatened, and is distributed from the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka to Indochina and the northern Malay Peninsula, although like many other Asian storks, it too has suffered great declines in numbers and is no longer found in many areas where it was once common.

Painted storks, Sungei Buloh;

(Photo by hiker1974)

Flock of painted storks, Upper Seletar;

(Photo by NatureInYourBackyard)

Milky stork (left) and painted stork (right), Sungei Buloh;

(Photo by chrisli023)

These are the 3 species of storks recorded in Singapore to date. The painted stork probably never occurred as far south as Johor and Singapore, while the milky stork is absent from old records as a native of Singapore's wetlands and mangroves. Both are best treated as feral species. Hence, if the burung ranggung that Serangoon is named for was indeed a stork, the best candidate remains the lesser adjutant.

(Photo by Mark Bakkers)

Sure, the lesser adjutant might be attractive in its own way, but it does make me glad that my own neighbourhood of Tampines was named after a tree.

![51festival-of-biodiversity_singapore_botanic_gardens_26may2012[bz]](http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8167/7293567168_c610c6fa09.jpg)

![09earth-day-cleanup-tanah-merah-28apr2012[xu-weiting]](http://farm9.staticflickr.com/8145/6981033486_3d27072383.jpg)

![28toddycats-training-festival-of-biodiversity-23may2012[ss]](http://farm8.staticflickr.com/7104/7260325940_c31fb7ef0b.jpg)